Civic engagement encompasses a broad range of activities related to democracy, from donating to charity to running for political office. It includes the work of long standing membership nonprofits, faith-based efforts, as well as new, technology-supported initiatives.

While there is a breadth and diversity of civic engagement efforts that donors can fund, we focus on three related forms of civic engagement. Each affect the five elements of a strong democracy and tie into our overall funder framework.

- Civic Membership: Joining voluntary associations fosters social cohesion and empowers citizens by aggregating individual voices. Community members are most effective in solving problems and holding institutions accountable when they act collectively.

- Deliberative Participation: Forums for public discourse lead to more informed citizens and richer communication between elected officials and their constituents, resulting in more responsive policy. Such forums have also been found to decrease partisanship.

- Voting: Sustained, broad-based participation in elections—local, state, federal, and primaries—enforces policymakers’ accountability to citizens and is the centerpiece of a democratic political system.

Together, these three forms constitute a vision of how citizens can participate in the democratic process. However, while increased participation is a boon to democracy, there is a link between participation and partisanship. The more ideologically polarized people are, the more likely they are to participate by voting, donating to campaigns, or writing to their member of Congress.[i] Modern political campaigning has been likened to a prisoner’s dilemma: the two parties engage in partisan rhetoric knowing it erodes trust and legitimacy because the stakes of elections are so high and partisan attacks are so effective at persuading and mobilizing voters.[ii] Since social cohesion is a key element in our framework for strengthening democracy, our guidance focuses on how civic organizations can offer an alternative, less polarizing pathway to political engagement.

Historically, civil society organizations such as parent-teacher associations, neighborhood associations, and unions provided a means for private citizens to band together to influence policy. As participation in civic organizations has declined and become more unequal, marginalized groups have seen their voice in the political process diminish. When examining rates of civic membership, use of political voice, and voting, there is pronounced inequality along lines of race and class.[iii] These discrepancies are reflected in the underrepresentation of these groups in political leadership and the degree to which their preferred policies are enacted.[iv] [v] Several of the nonprofits we feature in “We the People: Nonprofits Making an Impact” pay particular attention to elevating the voices of those from underrepresented communities.

Civic Membership

Civic membership has multiple benefits. In “Making Democracy Work,” Robert Putnam shows that higher civic membership predicts better government performance, even across geographies with identical political institutions.[vi] But Americans are far less likely to join a civic group, or even have friends over for dinner than they were during the middle of the 20th century.[vii] The percentage of people reporting that they were a member of at least one group (church, sports, professional, etc.) has steadily declined from 75% in 1974 to 62% by 2004.[viii] As voters increasingly engage with public affairs in isolation, the often partisan messages conveyed via mass media are more influential, fueling polarization and disengagement.

The League of Women Voters (LWV) offers a longstanding example of a nonprofit supporting civic membership. Founded in 1920, LWV has over 700 local chapters and 50,000 dues paying members. LWV’s autonomous local chapters offer citizens a platform for self-directed citizen engagement, while its state and national affiliates sponsor debates and advocate face to face with policymakers.

Joining organizations that participate in civic life is a habit that many Americans in recent generations have never developed, partially due to declining commitment to civics in public education.[ix] Service learning programs have proven effective in encouraging students’ civic engagement later in life.[x] For example, Generation Citizen provides middle and high school teachers with the curriculum, training, and support for a semester-long civics course that embeds civic participation into the classroom through actions such as contacting lawmakers and circulating petitions. Such early educational experiences empower citizens to become lifelong participants in the democratic process.[xi]

Deliberative Participation

Deliberative participation gives citizens an opportunity to express their views, moderates extreme voices, and exposes people to opposing viewpoints. For example, when members of a group are provided with balanced information and observe discussion rules that encourage self-reflection, participants become less extreme in their views and factual misconceptions are corrected, even in like-minded groups.[xii]

A number of barriers to widespread deliberation have emerged in recent years, such as scarcer face time with elected officials due to more populous districts and the sensationalizing and polarizing tendencies of web-based discourse. Nonprofits have employed a variety of strategies to encourage deliberation in this new context. Online congressional town halls, for instance, independently hosted and moderated by the Institute for Democratic Engagement and Accountability and the National Issues Forum lower barriers for participation, thereby attracting a more representative sample of constituents for healthier political discussion that can lead to responsive policy.[xiii]

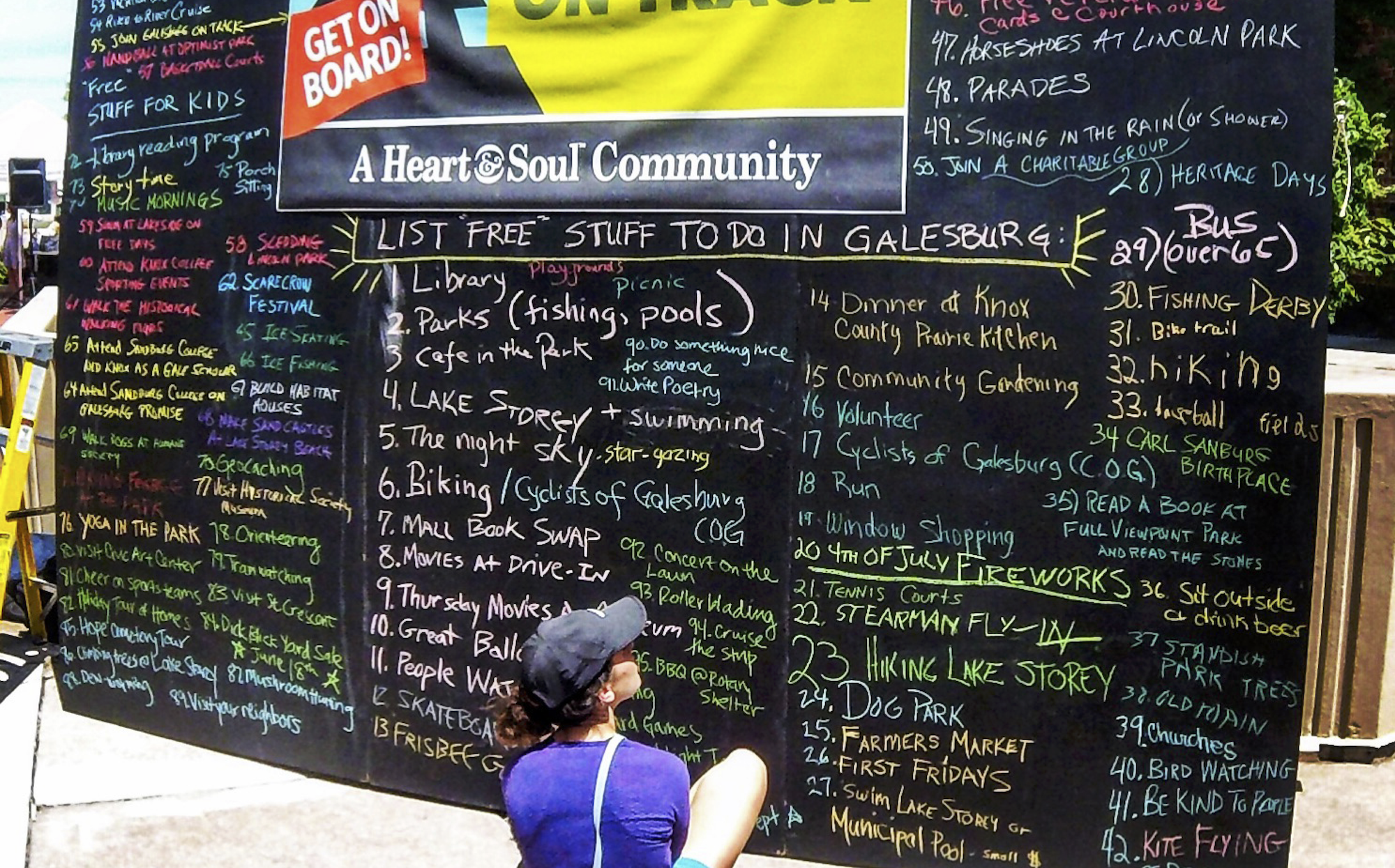

The Orton Family Foundation has developed a model for resident-driven town planning through its Community Heart & Soul program. The program has provided a way to reengage residents of towns and small cities that have been destabilized either by rapid growth or development or the loss of industry and population decline.

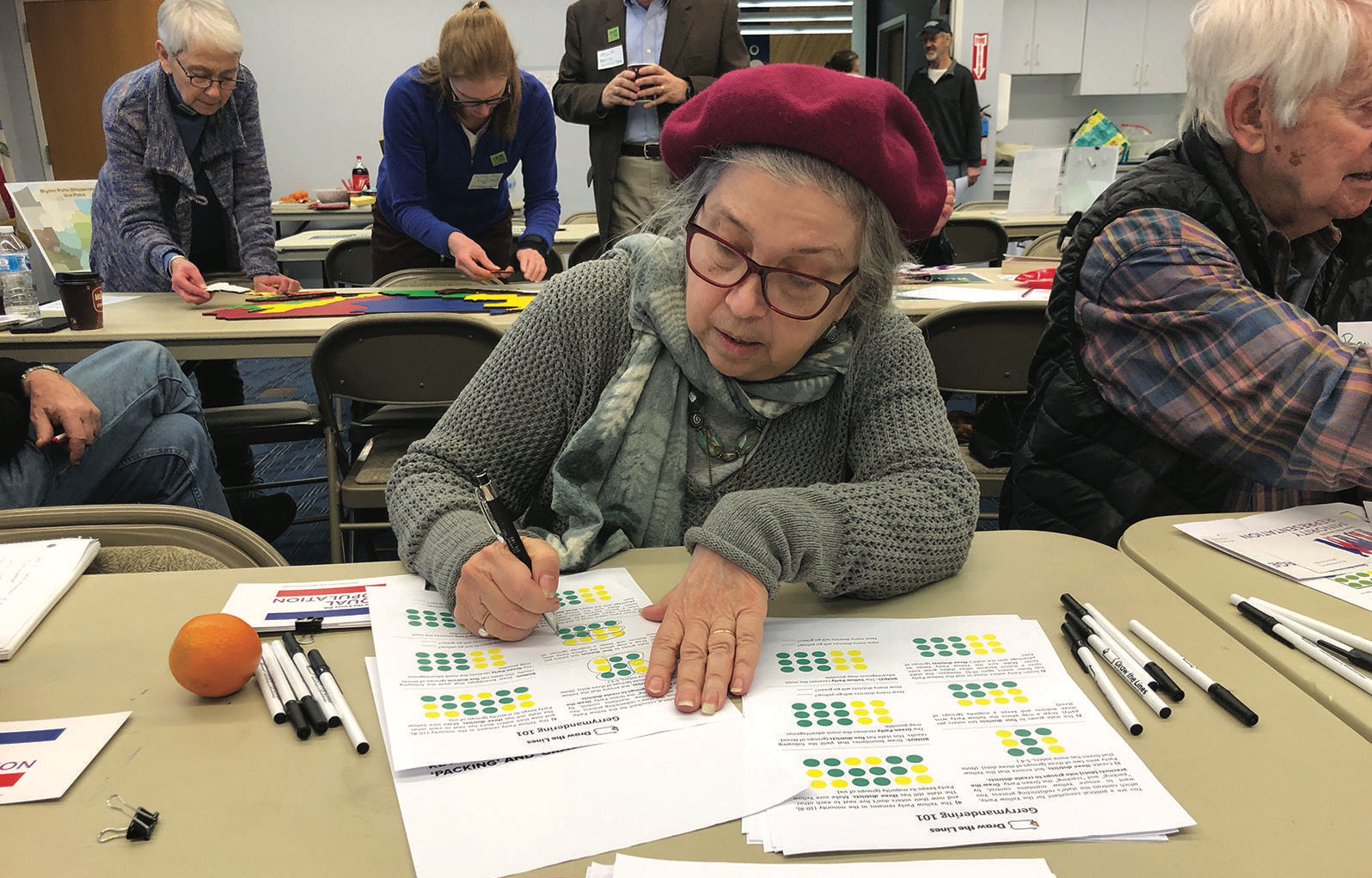

The Committee of Seventy’s Draw the Lines PA project shows how technology can be used in tandem with in-person engagement to foster broad, deliberative participation. Its statewide competition has engaged teams from high schools, colleges, and various civic organizations to give citizens a voice in Pennsylvania’s redistricting process.

Voting

Social networks are critical to voter turnout. As Meredith Rolfe writes, “campaign activity sets off a chain reaction among civic‐minded citizens whose decisions are largely conditional on the decisions of those around them.”[xiv] Voter engagement efforts that build relationships between an organization and its constituency develop long-term capacity to influence political outcomes.[xv]

Too often, voter engagement funding goes to last-minute efforts of volunteers during election years. Such volunteers “parachute in” to knock doors in the weeks before an election. More sustained engagement efforts can engage voters across and between multiple election cycles, and do so in a less partisan context than the final days of a presidential campaign. Civic membership and deliberative participation are two ways voters stay engaged outside of elections.

Technology can also increase voter engagement, especially when embedded in a social context. For example, the TurboVote Challenge encourages companies to register their employees and customers via the TurboVote app, which informs voters about registration deadlines, election days, and polling locations.

Increasing Civic Engagement: Nonprofits Making an Impact

Notes

[i] Pew Research Center. “Political Polarization in the American Public.” 2014. https://www.people-press.org/2014/06/12/political-polarization-in-the- american-public/

[ii] Gordon Kamer. “Hyper-Partisanship and the Prisoner’s Dilemma.” Harvard Political Review. 2018. http://harvardpolitics.com/united-states/hyper-partisanship-and-the-prisoners-dilemma/

[iii] Sidney Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady. “Voice and Equality.” 1995.

[iv] Nicholas Carnes. “The Cash Ceiling.” 2018.

[v] Martin Gilens. “Affluence and Influence: Economic Inequality and Political Power in America.” 2013.

[vi] Robert Putnam. “Making Democracy Work.” 1993.

[vii] Robert Putnam. “Bowling Alone.” 2001.

[viii] Tom W. Smith, Michael Davern, Jeremy Freese, and Michael Hout. “General Social Surveys, 1972-2016.” Data accessed from the GSS Data Explorer website at gssdataexplorer.norc.org.

[ix] Carnegie Corporation of New York, CIRCLE. “The Civic Mission of Schools.” 2003.

[x] Christine Celio, Joseph Durlak, and Allison Dymnicki. “A Meta-Analysis of the Impact of Service-Learning on Students.” Journal of Experiential Education. 2011. doi:10.5193/jee34.2.164

[xi] Sidney Verba, Kay Lehman Schlozman, and Henry E. Brady. “Voice and Equality.” 1995.

[xii] Kimmo Gronlund, Kaisa Herne, and Maija Setala. “Does Enclave Deliberation Polarize Opinions?” 2015.

[xiii] David Lazer, Michael Neblo, Kevin Esterling, and Kathy Goldschmidt. “Online Town Hall Meetings: Exploring Democracy in the 21st Century.” 2009.

[xiv] Meredith Rolfe. “Voter Turnout: A Social Theory of Political Participation.” 2013.

[xv] Hahrie Han. “A Program Review of the Promoting Electoral Reform and Democratic Participation Initiative of the Ford Foundation.” 2016. https://www.fordfoundation.org/media/2963/public-hanreport-apr2016.pdf